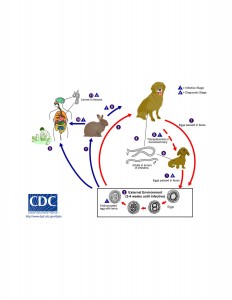

The life cycle of Toxocara roundworm species involves a predator and a prey animal. The predator host the adult stage of the roundworm in their intestine where the male and female roundworms reproduce sexually and produce eggs. For this reason the predator is termed the definitive host of Toxocara species. These eggs are not infectious when they leave their host with the faeces and have to mature for approximately five days to become infectious. Dogs and other canids are the definitive hosts of Toxocara canis and cats are the definitive hosts of Toxocara cati.

Dogs and other canids are the definitive hosts of Toxocara canis and cats are the definitive hosts of Toxocara cati.

The prey animals become infected by ingesting infectious Toxocara eggs. The eggs hatch in the intestine and release their larvae. These juvenile larvae penetrate the wall of the intestine and circulate in the blood until they lodge in the tissues where the larvae establish. These larvae are unable to grow in size or reproduce during the larval stage. When the definitive host specie ingest the infected prey animal including living larvae, the larvae grow to adult roundworms and establish in the intestine. For this reason the prey animals are termed the intermediate hosts of Toxocara.

The prey animals become infected by ingesting infectious Toxocara eggs. The eggs hatch in the intestine and release their larvae. These juvenile larvae penetrate the wall of the intestine and circulate in the blood until they lodge in the tissues where the larvae establish. These larvae are unable to grow in size or reproduce during the larval stage. When the definitive host specie ingest the infected prey animal including living larvae, the larvae grow to adult roundworms and establish in the intestine. For this reason the prey animals are termed the intermediate hosts of Toxocara.

A number of various vertebrates, including humans, and some invertebrates may become infected by Toxocara eggs. As humans are not prey animals and not eaten by dogs or cats, humans infected with the larval stage of Toxocara are termed accidental hosts.

The definitive host of Toxocara roundworms are mostly unaffected by harbouring the roundworms in their gut with the exception that the roundworm consume some of the nutrients passing by. In this way the definitive host will keep fit and able to spread the Toxocara eggs in the environment. Dogs are spreading the eggs exceptionally well by never defecating in the same place. Maximal spread of the Toxocara eggs is beneficial for the Toxocara species and the defecation behaviour of dogs are perfectly adapted to the interests of the Toxocara roundworm.

The intermediate host infected with Toxocara larvae may be affected in a number of ways. Toxocara canis larvae exhibit neurotrophic behaviour and the effects of Toxocara infection in the brain have been studied in mice and rats. (1) Mice infected by these larvae in their brain display a range of altered behaviours as decreased exploratory behaviour, spatial awareness, sensorimotor skills, shock avoidance, increased hyperactivity and decreased motor performance. In rats, learning and memory was affected. (1,2,3) The debilitation of the intermediate host of Toxocara cani facilitates the predation of the animal and benefits the predator as well as the Toxocara roundworm.

Clinical signs of human infection with Toxocara larvae include cough, fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, general malaise, weakness, rash, facial oedema, headache, abdominal pain, sleep and behaviour disorders, pharyngitis, pneumonia, wheezing, limb pains, cervical lymphadenitis and hepatomegaly. (4,5) Asthma and allergic manifestations may probably be caused by Toxocara infection, but the jury is still out due to little research. However, common features in allergic asthma and toxocariasis are inflammation of the airways, accumulation of eosinophils and induction of immunoglobulin E production. (4) Toxocara infection of the brain in humans are seldom diagnosed, but the infection may possibly cause hyperactivity and neuropsychological impairment. (2) Toxocara canis may invade the eye in humans and cause visual loss and blindness. Less harmful symptoms of human toxocarisasis is skin manifestations as pruritus sine materia, eczema and chronic urticaria. (5)

Time is long overdue to systematically examine to which extent infection with Toxocara larvae transmitted from dogs and cats is harmful to humans.

1. Holland CV, Hamilton CM. The significance of cerebral toxocariasis: a model system for exploring the link between brain involvement, behaviour and immune response. J Exp Biol 2013;216:78-83.

2. Holland CV, Hamilton CM. The significance of cerebral toxocariasis. In: Holland CV, Smith HV, eds. Toxocara: the enigmatic parasite. CABI Publishing, 2006; pp. 58-73.

3. Holland CV, Cox DM. Toxocara in the mouse: a model for parasite-altered behaviour? J Helminthol 2001;75:125-35.

4. Pinelli E, Dormans J, van Die I. Toxocara and asthma. In: Holland CV, Smith HV. Toxocara: the enigmatic parasite. CABI Publishing, 2006; pp. 42-57.

5. Piarroux R, Gavignet B, Hierso S, Humbert P. Toxocariasis and the skin. In: Holland CV, Smith HV. Toxocara: the enigmatic parasite. CABI Publishing, 2006; pp. 145-57.

Toxocara canis high resolution pdf

Sincere thanks to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Parasitic Diseases (CDC DPDx) for free use of illustrations.